Issued with Printed Papers of Session 1893-94.

|

|

BY E. GORDON DUFF.

| I |

/ p.2 /

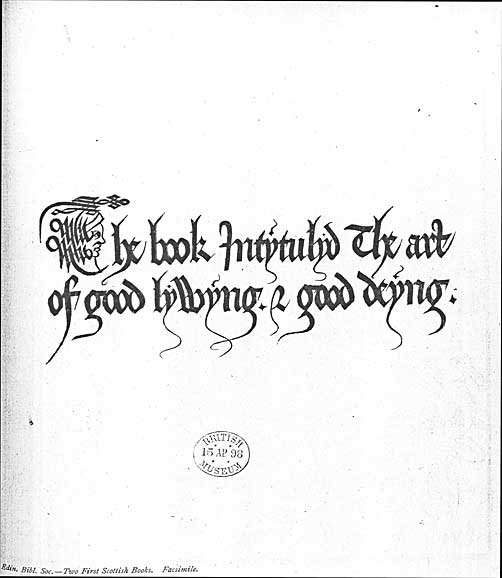

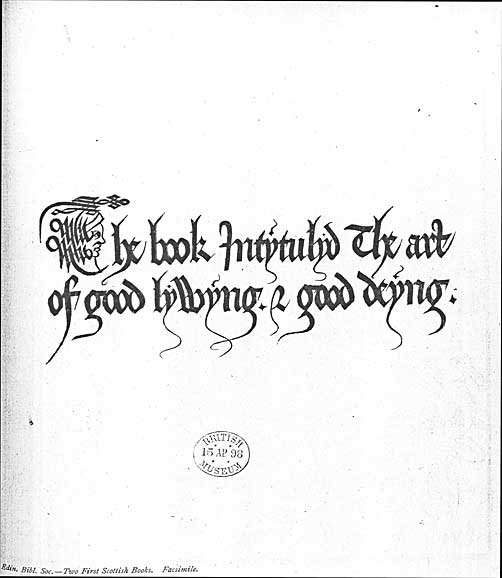

It begins on the recto of the first leaf:—

|

The book Intytulyd The art of good lyvyng & good deyng; |

|

The kalendayr of the shyppars. |

| ¶ | Heyr endyth the kalendar of shyppars translatyt of franch in englysh to the lowyng of almyghty god & of hys gloryows mother mary and of the holy cowrt of hywyn pren- tyt in parys the .xxiii. day of myng oon thow- sand.ccccc.&.iii. |

The last leaf is not known, but is almost certain to have contained Verard's device.

Throughout the book are numbers of cuts, none of them specially made for the edition, but taken from various other books. The larger and more important cuts had already been used in the editions of L'art de bien vivre et de bien mourir, issued by Verard in 1492, 1493, and 1496; and after having been used in this Calendar of 1503, they came over to England, and were used by Pynson in his edition of 1506, and they are found also in many of the later editions.

Collation a–m8; 96 leaves (1–96), one column, 40 lines to the page.

Two copies are known, one belonging to the Duke of Devonshire [bought in 1810 from the Roxburghe Sale for £180], which wants the last leaf, and another in the John Rylands Library, wanting sixteen leaves. A fragment of two leaves is amongst the Douce fragments at Oxford.

There is very little doubt that this book was printed by or for Anthony Verard. Unfortunately, the last leaf is wanting in both copies, so that we cannot tell whether it contained a printer's device. As the earlier book contains no notice of a printer or publisher beyond Verard's device on the last leaf, it is hardly an unjust surmise if we consider it probable that had the present book a last leaf it would contain Verard's device.

But there is one point especially to be noticed about the book, and that is that the type in which the greater part is printed is not known to have been used for any other book. When I say this I mean that no other book is known in this type; but I found some years ago a leaf, and, lately, fragments of some more leaves in the same type, and these fragments form portions of a book which is also very strongly linked with the history of Scottish literature. The leaves are from what is probably the first edition of Barclay's translation of Gringoire's Chasteau de Labour, and I have very little doubt that the edition was printed under Barclay's eye at Paris before he returned to England and took orders. As he is supposed to have returned about 1505, we may place these fragments about 1503-1504, which brings them into the same period as the other two books. Barclay's work, however, is not written in the Scottish tongue, or any approach to it, so that we may at once dismiss absolutely any idea that he was connected in any way with the other two books. His language was always un-provincial, and, indeed he gives us so very slight a clue to his nationality that, had it not been / p.5 / for the very painstaking and careful work of Mr Jamieson, he would probably by this time have been claimed for England.

Both these books are clearly the work of one man, and he was evidently a Scotchman; and when in 1508 the book was reprinted by Wynkyn de Worde, we have a preface from his translator and corrector, Richard Copland, who had a great knowledge of French, and there we find:—

. . . . "¶ Not long tyme passed I beynge in my chambre where as were many pamfletes and bokes whiche in avoydynge ydlenes moder of all vyces I ententyfly behelde; thynkynge to passe the longe wynters nyght, and sodeynly there came to my hand one of the sayd bokes of the shepeherdes kalender in rude and scottysshe language, whiche I redde, and perceyvynge the mater to be ryhht compendyous, and remembrynge howe the people desyre to here and se newe thynges I shewed the sayd boke unto my worshypful mayster Wynkyn de worde, at whose commaundement and instygacyon I Robert Coplande have me applyed dyrectly to translate it out of frensshe agayne in to our maternall tongue after the capacyte of myne understandynge accordynge to myne Auctoure."

What I have just quoted is from the third edition, and I have put it first because it plainly declares the language to be Scottish; but the translator or reviser of the second edition, printed by Richard Pynson in 1506, was doubtful about the language of the first edition, though he does not definitely say what he considered it to be. He says: "Here before tyme thys boke was prynted in parys in to corrupte englysshe and nat by no englysshe man wherfore these bokes that were brought into Englande no man coude understande." Now, if we can take this sentence as truthful "in substance and in fact," it shows us two curious things—first (though this is only implied), that the editor did not know that the version of 1503 was in Scottish, and secondly, that English people could not understand it.

As to the personality of the translator we have little to guide us. At the end of the Kalendar of Shepherdes he has added a chapter on the "Ten Christian Nations," not found in the French original, and says in the introduction to it: "I pretend in thys lytel traytte to speyk of maynay nacyons crestyens the qwych ar dywydyt in .x. queyr of I shal declayr after ys [this?] I have fond be wryt in the latyn tong and shal translayt in englysh after the capycyte of my lytel wnderstondyng and doyand thys yf I ar that yf pleys to at translaturs to excus my zowtheyd [youth?] in the qwych I am and amend my fawltes, for yf I haue faylltzyt I put me to al amendyng."

This passage, so far as it is possible to understand it, seems to show that the translator was young.

His knowledge of French was certainly very poor; for instance, he / p.6 / translates "Combien que vivre et mourir soit au plesir et volonte de nostre seigneur si doit," etc., by "How weeyl that leywyng et deyng to the pleasyr et wyl of owr lord shold man lyue," etc.

One small point in the book shows, I think, conclusively that the translator was a Scotchman. Speaking of the Latin nation, and mentioning the kings of Europe, he puts the King of Scotland first.

A facsimile of the Kalendar has lately been published, with "prolegomena," by Dr Oskar Sommar. His remarks, though voluminous, do not much advance our knowledge. He concludes thus:—

"Bearing in mind the existence of these intimate relations between the two countries [France and Scotland], we cannot be at all surprised to hear that, besides those young Scotchmen who went to Paris to pursue or to complete their studies, there were others who came over to learn a profession as, e.g., printing. It is more than probable that the translator of the Traytte and the Kalendayr was a young Scotchman of this description, who came into contact with Antoine Verard, the declared pbulisher of the Traytte, who most likely also published the Kalendayr. Verard had certainly no idea of the difference of English and Scotch, or he would never have ventured a speculation with so doubtful a success as the publication of the two books."

Dr Sommar seems to me to look at the matter in quite a wrong light. I do not for a moment suppose that the books were intended for sale in England. They were printed in the Scottish language for sale in Scotland.

Again, the excessive number of misprints, often of the most careless and stupid description, and the rendering of "&" by "et," surely point to the fact that the book was set up by Frenchmen, and that there was no Scotchman in the office either to assist in printing or to correct the proofs.

We know from the colophon of the Traytte that the translator was in Paris in May 1503; beyond this we have no information.

Issued with Printed Papers of Session 1893-94.

|

|