ILLUSTRATIONS

OF THE

LIFE OF SHAKESPEARE.

| THE SAND HEAPED BY ONE FLOOD IS SCATTERED BY ANOTHER, BUT THE ROCK ALWAYS CONTINUES IN ITS PLACE. THE STREAM OF TIME, WHICH IS CONTINUALLY WASHING THE DISSOLUBLE FABRICS OF OTHER POETS, PASSES WITHOUT INJURY BY THE ADAMANT OF SHAKESPEARE.—Dr. Johnson. |

ILLUSTRATIONS

OF THE

LIFE OF SHAKESPEARE.

ON A

THE GREAT DRAMATIST.

PART THE FIRST.

PUBLISHED BY MESSRS. LONGMANS, GREEN & CO.

1874.

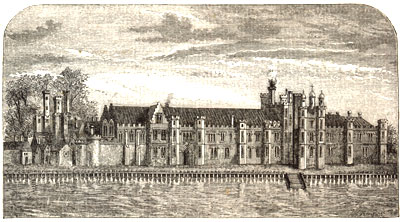

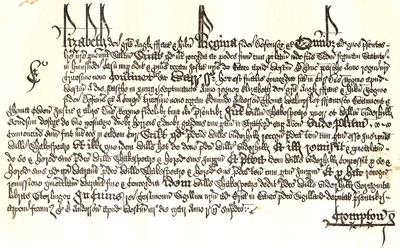

THE remains of New Place, a sketch of which is engraved on the title-page, are typical of the fragments of the personal history of Shakespeare which have hitherto been discovered. In this respect the great dramatist participates in the fate of most of his literary contemporaries, for if a collection of the known facts relating to all of them were tabularly arranged, it would be found that the number of the ascertained particulars of his life reached at least the average. At the present day, with biography carried to a wasteful and ridiculous excess and Shakespeare the idol not merely of a nation but of the educated world, it is difficult to realize a period when no interest was taken in the events of the lives of authors, and when the great poet himself, notwithstanding the immense popularity of some of his works, was held in no general reverence. It must be borne in mind that actors then occupied an inferior position in society, and even the vocation of a dramatic writer was scarcely considered respectable. The intelligent appreciation of genius by individuals was not sufficient to neutralize in these matters the effect of public opinion and the animosity of the religious world; all circumstances thus uniting to banish general interest in the history of persons connected in any way with the stage. This biographical indifference continued for many years, and long before the season arrived for a real curiosity to be taken in the subject, the records from which alone a satisfactory memoir could have been constructed had disappeared. At the time of Shakespeare's decease, non-political correspondence was rarely preserved, elaborate diaries were not the fashion, and no one, excepting in semi-apocryphal collections of jests, thought it worth while to record many of the sayings and doings, or to delineate at any length the characters of actors and dramatists, so that it is generally by the merest accident that any particulars of interest respecting them have been recovered.

In the absence of some very important discovery the general and intense desire to penetrate the mystery which surrounds the personal history of Shakespeare cannot be wholly gratified. Something, however, may be accomplished in that direction by a diligent and critical study of the materials now accessible, especially if care be taken to avoid the temptation of endeavouring to decipher his inner life and character through the media of his works. The genius which so rapidly converted the dull pages of a novel or history into an imperishable drama was transmuted into other forces in actual life, as may be gathered even from the scanty records of his biography which still remain. Let these latter be studied in that truest spirit of criticism / p.vi / which deals with facts in preference to conjecture and sentiment, regard being ever watchfully paid to the circumstances by which he was surrounded. A minute examination of those circumstances is essential to the effective study not merely of the personal but of the literary history of the great poet. It will dissipate many an illusion, amongst others the propriety of criticism being grounded upon a reverential belief in the unvarying perfection of Shakespeare's dramatic art. He indeed unquestionably obtained a complete mastery over that art at an early period of his literary career, but his control over it was continually liable to be governed by the customs and exigencies of the ancient stage, so much so that in not a few instances the action of a scene was diverted for the express purpose of complying with those necessities. Hence amongst other reasons the importance of a study of the history of the contemporary stage, which constitutes so prominent a feature in the following pages, and without which it is impossible to understand the conditions under which Shakespeare acted and wrote. It should be remembered that his dramas were not written for posterity, but as a matter of business, never for his own speculation but always for that of the managers of his own day, the choice of subject being occasionally dictated by them or by patrons of the stage. Those works in which the perfection of art was attained may have been the fruits of express or cherished literary design, but all his writings were the products of an intellect which was applied to authorship as the readiest path to material advancement; his task having been to construct out of certain given or selected materials successful dramas for the audiences of the day, some for the polished few, others for the multitude. It is not pretended that he did not invariably take an earnest interest in his work, his intense sympathy with each character forbidding such an assumption; but simply that his tastes were subordinated when necessary to his duty to his employers. If a play were required at short notice, it was hurriedly written. If the managers considered that the popular feeling was likely to encourage, or if an influential patron or the Court desired, the production of a drama on some special theme, it was composed to order on that subject no matter how repulsive the character of the plot or how intrinsically it was unfitted for dramatic purposes; and, again, it is not improbable that some of Shakespeare's works, perfect in their art when represented before a select audience, might have been deteriorated by their adaptation to the public stage, and that in some instances the later copies only have been preserved. From some of these causes may have arisen inequalities in taste and art which otherwise appear to be inexplicable, and which would doubtlessly have been removed had Shakespeare lived to have given the public an edition of his works during his retirement at Stratford-on-Avon. The Burbages had no conception of his intellectual supremacy, and, if they had, it is certain that they would not have deviated on that account from the course they were in the habit of pursuing. In their estimation, however, he was merely, to use their own words, a "deserving man," an effective actor and a popular writer, one who would not have been considered so valuable a member of their staff had he not also worked as a practical man of business, knowing that the success of the theatre was identified with his own, and that within certain limits it was necessary that his art should be regulated by expediency. Neither does it appear at all probable that he could have had time, under the conditions in which he worked, for the studied application of those subtle devices underlying his art which are attributed to his sagacity by the philosophical critics, / p.vii / and some of which, it is amusing to notice, may be equally observed, if they exist at all, in the original plot-sources of his dramas. Entertaining these views, no space in the present work will be devoted to the examination of conjectural generic ethical designs, imaginary moral unities and such like. It is one thing to admit that Shakespeare's art was frequently influenced by the emergencies of the stage,— another that he would have gratuitously permitted it to have been controlled by the necessity of blending a variety of actions in subjection to one leading moral idea or by other similar limitations. The phenomenon of a moral unity is not to be found either in nature or in the works of nature's poet, whose truthful and impartial genius could never have voluntarily endured a submission to a preconception which involved violent deviations from the course prescribed by his sovereign knowledge of human nature and the human mind.

The literary history of Shakespeare cannot of course be perfected until the order in which he composed his works has been ascertained, but unless the books of the theatrical managers or licensers of the time are discovered it is not likely that the exact chronological arrangement will be determined. The dates of some of his productions rest on positive testimony or distinct allusions, and these are stand-points of great value. In respect, however, to the majority of them the period of composition has unfortunately been merely the subject of refined and useless conjecture. Internal evidences of construction and style, obscure contemporary references, and metrical or grammatical tests can very rarely in themselves be relied upon to establish the year of authorship. Specific phases of style or metre necessarily had periods of commencement in Shakespeare's work, but so long as those epochs are merely conjectural no real progress is made in the enquiry. Nor as a rule are the results obtained from æsthetic criticism, which depend to some extent upon the individual sentiment of the critic, of much greater certainty. No sufficient allowances appear to be made for the high probability of the intermittent use of various styles during the long interval which elapsed after the era of comparative immaturity had passed away, and in which, so far as constructive and delineative power was concerned, there was neither progress nor retrogression. Shakespeare's genius arrived at maturity with such celerity it is perilous to assert from any kind of internal evidence alone what he could not have written at any particular subsequent period, and style frequently varies not only with the subject but with the purpose of authorship. It may be presumed for instance that the diction and construction of a drama written for performance at the Court might be essentially dissimilar from those of a play of the same date composed for the ordinary stage, where the audiences were of a more promiscuous character and the usages and appliances of the actors in many respects of a different nature. Bearing these probabilities in mind, conjecture will generally be avoided in discussing the chronological order, but several new evidences of importance will be produced in this as well as in most of the other cognate branches of criticism.

Further occasional discoveries of isolated facts respecting the poet and his writings may still be reasonably expected. If no more are made, it will not be for lack of opportunity, for unusual facilities have been and are being given to me in the collection of materials. Private and other libraries, family archives, municipal records and official collections have been made accessible with a kind and ready liberality for which I cannot feel too grateful.

The main design of the present work is a critical investigation into the truth or purport of every recorded incident in the personal and literary history of Shakespeare; but it is proposed to add notices of his surroundings, that is to say, amongst others, of the members of his family, the persons with whom he associated, the books he used, the stage on which he acted, the estates he purchased, the houses and towns in which he resided and the country through which he travelled. The consideration of these and similar topics will not be without its biographical value. It will bring us nearer to a knowledge of Shakespeare's personality if we can form even an approximate idea of the condition of England and its people in his own day, the sort of places in which he lived, how he made his fortune, the occupations and social positions of his relatives and friends, the nature of the ancient stage and the usages of contemporary domestic life.

It only remains to add that no chronological or other specific order has been attempted in the following pages. The arrangement of the various essays is the fortuitous result of my own convenience or humour, the compilation of this work being in fact merely one of the amusements of the declining years of life. It is followed, as all recreations should be, earnestly and lovingly, but in complete subjection to the vicissitudes of one's own temperament and inclination.

No. 11, TREGUNTER ROAD, LONDON;

September, 1874.

SYMBOLS AND RULES IN COPIES AND EXTRACTS.

2. The division between lines of poetry which are quoted in the text is indicated by the parallel marks

3. In extracts from printed books or manuscripts written in the English language, the original mode of spelling is retained excepting in the cases of the ancient forms of the consonants j and v and the vowels i and u, but they are modernized in other respects, such as in the punctuation, use of capitals, &c. It may be well to observe that, in documents of the Shakespearean period, the letters ff at the commencement of a word merely stand for a capital F, and that it is not always possible to decide whether a transcriber of that time intended or to be a contraction for our or whether he merely used it for or. There is often also a difficulty in ascertaining if a final stroke of a word is an e or simply a flourish.

4. In special instances, denoted by the letters V. L., the original texts are followed in every particular with minute accuracy.

5. The orthography of old Latin documents is generally followed, e.g., e for æ, capud for caput, set for sed, nichil for nihil, &c. In the Latin as well as in the English extracts errors which are obviously merely clerical ones are occasionally corrected.

ILLUSTRATIONS

LIFE OF SHAKESPEARE.

THE FIRST PART.

THE precise time at which Shakespeare commenced his professional career in London is not known, but it must be assigned to some period after May, 1583, and before the year 1592. He left Stratford-on-Avon after the birth of his eldest child, Rowe distinctly stating that, when he fled to the metropolis, "he was oblig'd to leave his business and family in Warwickshire," Life, ed. 1709, p. 5. In 1592, as we learn from the indisputable testimony of Greene, he was one of the actors and was also engaged in remodelling some of the dramas of the time. According to the most reliable authorities, Shakespeare held at first a subordinate position in the theatre. A person named Dowdall, who visited the Church of the Holy Trinity at Stratford-on-Avon early in the year 1693, gives the following interesting notice of the traditional belief, then current in the poet's native county, respecting this incident in his life, — "the clarke that shew'd me this church is above eighty years old; he says that this Shakespear was formerly in this towne bound apprentie

At the period of Shakespeare's arrival in London, any reputable kind of employment was obtained with considerable difficulty. There is an evidence of this in the history of the early life of John Sadler, a native of Stratford-on-Avon and one of the poet's contemporaries, who tried his fortunes in the metropolis under similar though less discouraging circumstances. This youth, upon quitting Stratford, "join'd himself to the carrier, and came to London, where he had never been before, and sold his horse in Smithfield; and, having no acquaintance in London to recommend him or assist him, he went from street to street, and house to house, asking if they wanted an apprentice, and, though he met with many discouraging scorns and a thousand denials, he went on till he light on Mr. Brokesbank, a grocer in Bucklersbury, who, though he long denied him for want of sureties for his fidelity, and because the money he had (but ten pounds) was so disproportionable to what he used to receive with apprentices, yet, upon his discreet account he gave of himself and the motives which put him upon that course, and promise to compensate with diligent and faithfull service whatever else was short of his expectation, he ventured to receive him upon trial, in which he so well approved himself that he accepted him into his service, to which he bound him for eight years." This narrative is or was preserved in a manuscript written by Sadler's daughter, but it is here taken from extracts from the original which were published in the Holy Life of Mrs. Elizabeth Walker, 8vo. Lond. 1690, pp. 10, 11. It is to be gathered, from the accounts given by Castle and Rowe, that Shakespeare, a fugitive, leaving his native town unexpectedly, must have reached London more unfavourably situated than Sadler, although the latter experienced so much trouble in finding suitable occupation. At all events, there would have been greater difficulty in Shakespeare's case in accounting satisfactorily to employers for his sudden departure from home. That he was also nearly, if not quite, moneyless, is to be inferred from tradition, the latter supported by the ascertained fact of the adverse circumstances of his father at the time rendering it impossible for him to have received effectual assitance from his parents; nor is there any reason for believing that he was likely to have obtained substantial aid from the relatives of his wife. Johnson no doubt accurately reported the tradition of his day, when, in 1765, he stated that Shakespeare "came to London a needy adventurer, and lived for a time by very mean employments," Preface to his Edition of Shakespear's / p.3 / Plays, 1765, separate edition, p. 41. To the same effect is the earlier testimony given by the author of Ratseis Ghost or the Second Part of his Madde Prankes and Robberies, 1606, where the strolling player, in a passage reasonably believed to refer to Shakespeare, says, speaking of actors, "I have heard, indeede, of some that have gone to London very meanly, and have come in time to be exceeding wealthy." The author of the last named tract was evidently well acquainted with the theatrical gossip of his day, and the chapter in which this passage occurs is so extremely curious, including other covert allusions, some possibly to Shakespeare himself, it is given at length in the Appendix, pp. 84-86.

The stage was in those days one of the few professions which required no capital and little preparation; but it does not follow that an inexperienced youth, fresh from the provinces, would easily have gained employment at once on the metropolitan boards even as a supernumerary. The quotations above given from Johnson's Preface and Ratseis Ghost seem to indicate that his earlier occupation was something of a meaner character. A traditional story was current about the middle of the last century, according to which it would appear that Shakespeare, if connected in any sort of manner with the theatre immediately upon his arrival in London, could only have been engaged in a servile capacity, and that there was, in the career of the great poet, an interval which some may consider one of degradation, to be regarded with either incredulity or sorrow. Others may, with more reason and without reluctance, receive the tradition as a testimony to Shakespeare's practical wisdom in accepting any kind of honest occupation in preference to starvation or mendicancy, and cheerfully making the best of the circumstances by which he was surrounded. The earliest record of the anecdote which is known to be extant is a manuscript note preserved in the University Library, Edinburgh, written about the year 1748, in which the tale is narrated in the following terms, — "Sir William Davenant, who has been call'd a natural son of our author, us'd to tell the following whimsical story of him; — Shakespear, when he first came from the country to the play-house, was not admitted to act; but as it was then the custom for all the people of fashion to come on horseback to entertainments of all kinds, it was Shakespear's employment for a time, with several other poor boys belonging to the company, to hold the horses and take care of them during the representation; — by his dexterity and care he soon got a great deal of business in this way, and was personally known to most of the quality that frequented the house, insomuch that, being obliged, before he was taken into a higher and more honorable employment within doors, to train up boys to assist him, it became long afterwards a usual way among them to recommend themselves by saying that they were Shakespear's boys." Shakespeare is here mentioned as one of "several poor boys belonging to the company," a statement which agrees with the earliest traditions that have been recorded, although he could not have been strictly considered a boy at the time. The inference seems to be that he was engaged in an occupation usually assigned to mere youths. The writer assumes it as an established fact that, on his arrival in London, he proceeded at once to the theatre in search of employment. "This William," grotesquely observes Aubrey, was "naturally inclined to poetry and acting." A taste for the drama had probably been imbibed in his early youth at Stratford-on-Avon, where, at that time, various companies of itinerant players at least occasionally, and perhaps frequently, exhibited their performances. The few recorded notices of the latter are restricted to those which took place at the [This continues on page 6.]

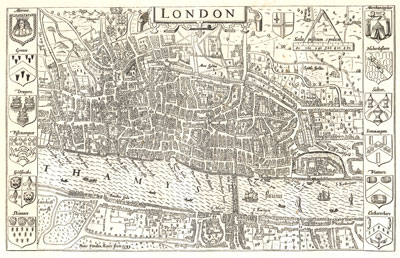

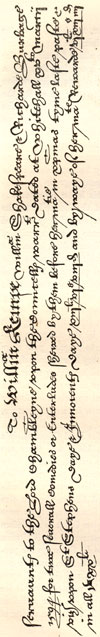

There are numerous engravings which are stated to be plans of the metropolis as it existed in the latter part of the reign of Queen Elizabeth, but the only one of undoubted accuracy is that which was engraved by Pieter Vanden Keere in 1593 from a drawing made by John Norden, the ablest surveyor of the day. It appears that Norden's survey was executed, or at least completed, in the same year, the following memorandum, — Joannes Norden Anglus descripsit anno 1593, — being inserted after the list of references. The copy of this plan here given has been carefully taken from a fine example of the original engraving of 1593. There are several imitations of it, and one so-called facsimile, all of which are inaccurate and worthless. Annexed to Norden's plan is the following list of streets and buildings, — a. Bushops gate streete; b. Papie; c. Alhallowes in the wall; d. S. Taphyns; e. Sylver streete; f. Aldermanburye; g. Barbican; h. Aldersgate streete; i. Charterhowse; k. Holborne Conduct; l. Chauncery lane; m. Temple barr; n. Holbourn; o. Grayes Inn lane; p. S. Androwes; q. Newgate; r. S. Jones; s. S. Nic. shambels; t. Cheap syde; u. Bucklers burye; w. Brodestreete; x. The stockes; y. The Exchannge; z. Cornehill; 2.![]() Colmanstreete; 3. Bassings hall; 4. Honnsditche; 5. Leaden hall; 6. Gratious streete; 7. Heneage house; 8. Fancshurche; 9. Marke lane; 10. Minchyn lane; 11. Paules; 12. Eastcheape; 13. Fleetstreete; 14. Fetter lane; 15. S. Dunshous; 16. Themes streete; 17. London stone; 18. Olde Baylye; 19. Clerkenwell; 20. Winchester house; 21. Battle bridge; 22. Bermodsoy

Colmanstreete; 3. Bassings hall; 4. Honnsditche; 5. Leaden hall; 6. Gratious streete; 7. Heneage house; 8. Fancshurche; 9. Marke lane; 10. Minchyn lane; 11. Paules; 12. Eastcheape; 13. Fleetstreete; 14. Fetter lane; 15. S. Dunshous; 16. Themes streete; 17. London stone; 18. Olde Baylye; 19. Clerkenwell; 20. Winchester house; 21. Battle bridge; 22. Bermodsoy![]() streete.

streete.

This extremely curious and valuable plan enables us to form a correct notion of the extent, and a tolerably effective idea of the general aspect, of London as it appeared in the early years of Shakespeare's residence in the metropolis. The circular building in Southwark, noted as "the play-howse," is the Rose Theatre. It is the earliest representation of an English theatre known to exist. The Theatre and the Curtain stood in the fields to the left of the road which leads upwards from Bishopsgate, but most unfortunately the limit of the plan in that direction just suffices for the exclusion of those interesting structures.

There are but two other surveys of London belonging to the reigns of Elizabeth and James which can be considered to be of any authority. One of these is a very large one of uncertain date, executed on wood, and generally attributed to Aggas. It was first issued in the time of Queen Elizabeth and reproduced in the reign of her successor. The other plan is an engraving on a much smaller scale, published by Braun at Cologne in 1572 from a survey evidently made before 1561, the steeple of St. Paul's, destroyed in that year, being introduced. Neither of these maps appear to be copies of absolutely original surveys taken for the object of publication, there being indications which lead to the conclusion either that they are alterations of a plan which was executed some years previously, or that the latter was used in their formation. The larger map is the only one of the time which represents the City with minuteness of detail, and it is unfortunate that its value should be impaired by this uncertainty. That there is much, however, in it on the fidelity of which reliance can be placed is unquestionable. The survey of the locality in which the Theatre and Curtain were situated must have been taken before 1576, the year in which the former was erected, for the artist engaged in a plan on such a large scale could not have failed to have introduced so conspicuous a building, had it then been in existence.

Guildhall under the immediate patronage of the Corporation, and to which the inhabitants were admitted without payment; but there were no doubt numerous other representations given in the town.

The same tradition is related by the writer of the Life of Shakespear, published in Cibber's Lives of the Poets of Great Britain and Ireland, 1753, i. 130-131, a collection only partially the work of Theophilus Cibber, and professedly "compiled from ample materials scattered in a variety of books, and especially from the manuscript notes of the late ingenious Mr. Coxeter and others collected for this design." The author of this biographical account of Shakespeare has been generally assumed, but without direct evidence, to be Robert Shiels, a person who was certainly associated with Cibber in the preparation of some other parts of the work. He introduces the tradition now under consideration in the following manner,—"I cannot forbear relating a story which Sir William Davenant told Mr. Betterton, who communicated it to Mr. Rowe; Rowe told it Mr. Pope, and Mr.Pope told it to Dr. Newton, the late editor of Milton, and from a gentleman who heard it from him, 'tis here related. Concerning Shakespear's first appearance in the playhouse;— When he came to London, he was without money and friends, and being a stranger he knew not to whom to apply, nor by what means to support himself. At that time, coaches not being in use, and as gentlemen were accustomed to ride to the playhouse, Shakespear, driven to the last necessity, went to the playhouse door, and pick'd up a little money by taking care of the gentlemen's horses who came to the play. He became eminent even in that profession, and was taken notice of for his diligence and skill in it; he had soon more business than he himself could manage, and at last hired boys under him, who were known by the name of Shakespear's boys. Some of the players, accidentally conversing with him, found him so acute, and master of so fine a conversation that, struck therewith, they and![]() recommended him to the house, in which he was first admitted in a very low station, but he did not long remain so, for he soon distinguished himself, if not as an extraordinary actor at least as a fine writer."

recommended him to the house, in which he was first admitted in a very low station, but he did not long remain so, for he soon distinguished himself, if not as an extraordinary actor at least as a fine writer."

The gentleman who heard the story from Dr. Newton was Dr. Johnson, one of his schoolfellows, and it is told as follows by the latter, apparently as an independent version, in the edition of Shakespeare which appeared in the year 1765,—"To the foregoing accounts of Shakespear's life I have only one passage to add, which Mr. Pope related as communicated to him by Mr. Rowe.—In the time of Elizabeth, coaches being yet uncommon and hired coaches not at all in use, those who were too proud, too tender or too idle to walk, went on horseback to any distant business or diversion. Many came on horseback to the play, and when Shakespear fled to London from the terrour of a criminal prosecution, his first expedient was to wait at the door of the play-house, and hold the horses of those that had no servants that they might be ready again after the performance. In this office he became so conspicuous for his care and readiness, that in a short time every man as he alighted called for Will Shakespear, and scarcely any other waiter was trusted with a horse while Will Shakespear could be had. This was the first dawn of better fortune. Shakespear, finding more horses put into his hand than he could hold, hired boys to wait under his inspection, who, when Will Shakespear was summoned, were immediately to present themselves, 'I am Shakespear's boy, sir.' In time Shakespear found higher employment, but as long as the practice of riding to the play-house continued the waiters that held the horses retained the appellation of Shakespear's Boys."

The anecdote is told somewhat differently by Jordan, a native of Stratford-on-Avon, in a manuscript written about the year 1783,—"Some relate that he had the care of gentlemen's horses, for carriages at that time were very little used; his business, therefore, say they, was to take the horses to the inn and order them to be fed until the play was over, and then see that they were returned to their owners, and that he had several boys under him constantly in employ, from which they were called Shakespear's boy's." It may be doubted if this be a correct version of any tradition current at the time it was written, Jordan having been in the habit of recording the Shakespearean tales with fanciful additions of his own. Gentlemen's horses in Shakespeare's days were more hardy than those of modern times, so that stables or sheds for them, during the two hours the performance then lasted, were not absolute necessities. At the same time it is worth recording that there were taverns, with accommodation for horses, in the neighbourhood of the theatres at Shoreditch. A witness, whose deposition respecting some land in the immediate locality was taken in 1602, states that he recollected, in years previously, "a greate ponde wherein the servauntes of the said Earle, and diverse his neighbours inholders, did usually wasshe and water theire horses, which ponde was commonly called the Earles horsepond." The nobleman here mentioned was the Earl of Rutland.

There is another and much simpler version of the anecdote recorded in the Monthly Magazine, in 1818, on the authority of an inhabitant of Stratford-on-Avon, who was one of the descendants from the poet's sister. It is given in the following words,—"Mr. J. M. Smith said he had often heard his mother state that Shakspeare owed his rise in life, and his introduction to the theatre, to his accidentally holding the horse of a gentleman at the door of the theatre on his first arriving in London; his appearance led to enquiry and subsequent patronage;" Monthly Magazine, February, 1818, repeated in Moncrieff's Guide, ed. 1822, p. 227; ed. 1824, p. 25. The mother of J. M. Smith was, according to a pedigree compiled by Wheler, the son of Mary Hart, who had married one William Smith. This Mary was, on the same authority, the daughter of the George Hart who married Sarah Mumford in the year 1729. She was the fifth in descent from Joan Shakespeare, the sister of Shakespeare. Versions of any tradition, however, respecting the great dramatist which cannot be traced beyond the chief era of the commencement of Shakesperean deceptions, the Stratford Jubilee of 1769, should be received with the utmost caution, especially if emanating from Warwickshire. The narratives of Jordan and Smith must be regarded as evidences which are at least of a questionable character.

The precise interpretation to be given to the term serviture, in Dowdall's narrative, is a matter of uncertainty. It may mean simply an attendant or servant, in the modern acceptation of the latter word, or what was formerly called a hireling. Henslowe, in 1597, speaks of a hireling actor, who was engaged at ten shillings a week when in London and five shillings a week when in the country, as "a covenaunt servant." It seems all but certain that Shakespeare commenced his real theatrical career as one of the hirelings or supernumeraries. The question is whether there is sufficient evidence to enable us to conclude that he was previously connected with the theatre in a still lower position. There appears to be valid testimony in favour of this opinion, and, if this be conceded, there is no sufficient obstacle to prevent the reception of the belief, however greatly the notion may now disturb our sentimental views of the career of the great dramatist, that in the first instance he / p.8 / had some engagement which in one way or other was connected with the protection of the horses of visitors during the performances, a duty for which his previous country life must have rendered him well fitted.

It has been and is the fashion with most biographers to discredit the horse tradition entirely, but that it was originally related by Sir William Davenant, and belongs in some form to the earlier half of the seventeenth century, cannot reasonably be doubted. The circumstance of the anecdote being founded upon the daily practice of numerous gentlemen riding to the theatres, a custom obsolete after the Restoration, is sufficient to establish the antiquity of the story. In a little volume of epigrams by Sir John Davis, printed at Middleborough in or about the year 1599, a man of inferior position is ridiculed for being constantly on horseback, imitating in that respect persons of higher rank,—"He rides into the fieldes playes to behold." Ben Jonson, in the Induction to Cynthia's Revels, first acted in the year 1600, also alludes to the ordinary use of horses by visitors to theatres (Workes, ed. 1616, p.184); so does Decker in his Guls Horne-book, 1609; and a later reference to the practice occurs in Brome's Court Beggar, a comedy acted at Drury-Lane Theatre in the year 1632. Many writers have rejected the tradition mainly on the ground that, although it was known to Rowe, he does not allude to it in his Life of Shakespeare, 1709; but there is no improbability in the supposition that the story was not related to him until after the publication of that work, the second edition of which in 1714 is a mere reprint of the first. Other reasons for the omission may be suggested, but even if it be conceded that the anecdote was rejected as suspicious and improbable, that circumstance alone cannot be decisive against the opinion that there may be a particle of truth in it. This is, indeed, all that is contended for. Few would be disposed to accept the story literally as related by Cibber, but when it is considered that the tradition must be a very early one, that its genealogy is respectable, and that it harmonizes with the general old belief of the great poet having, when first in London, subsisted by "very mean employments," little doubt can fairly be entertained that it has at least in some way or other a foundation in real occurrences. It should also be remembered that horse-stealing was one of the very commonest offences of the period, and one which was probably stimulated by the facility with which delinquents of that class obtained pardons. The safe custody of a horse was a matter of serious import, and a person who had satisfactorily fulfilled such a trust would not be lightly estimated. The theatres of the suburbs, observes a puritanical Lord Mayor of London in the year 1597, are "ordinary places for vagrant persons, maisterles men, thieves, horse-stealers, whoremongers, coozeners, conycatchers, contrivers of treason and other idele and daungerous persons to meet together and to make theire matches, to the great displeasure of Almightie God and the hurt and annoyance of her Majesties people, which cannot be prevented nor discovered by the governors of the Citie for that they ar owt of the Citiees jurisdiction," City of London MSS.

No one has recorded the name of the first theatre with which Shakespeare was connected, but if, as is almost certain, he came to London some few years before the notice of him by Greene in 1592, there were at the time of his arrival only two theatres in the metropolis, both of them on the north of the Thames. The earliest theatre on the south was the Rose, the erection of which was contemplated about the year 1586, but it would seem from Henslowe's Diary that the building was not opened till early in 1592. The circus at Paris Garden, though perhaps occasionally used for / p.9 / dramatic performances, was not a regular theatre. Admitting, however, the possibility that companies of players could have hired the latter establishment, there is good reason for concluding that Southwark was not the locality alluded to in the Davenant tradition. The usual mode of transit for those Londoners who desired to attend theatrical performances in Southwark, was certainly by water. The boatmen of the Thames were perpetually asserting at a somewhat later period that their living depended on the continuance of the Southwark, and the suppression of the London, theatres. Some few of the courtly members of the audience, perhaps for the mere sake of appearances, might occasionally have arrived at their destination on horse-back, having taken what would be to most of them the circuitous route over London Bridge; but the large majority would select the more convenient passage by boat. The Southwark audiences mainly consisted of Londoners, for in the then sparsely inhabited condition of Kent and Surrey very few could have arrived from those counties. The number of riders to the Bankside theatres must, therefore, always have been very limited, too much so for the remunerative employment of horse-holders, whose services would be required merely in regard to the still fewer persons who were unattended by their lackeys. The only theatres upon the other side of the Thames, when the poet arrived in London, were the Theatre and the Curtain, for, notwithstanding some apparent testimonies to the contrary, the Blackfriars' Theatre, as will be afterwards shown, was not then in existence. It was to the Theatre or to the Curtain that the satirist alluded when he speaks of the fashionable youth riding "into the fieldes playes to behold." Both these theatres were situated in the parish of Shoreditch, in the fields of the Liberty of Halliwell, in which locality, if the Davenant tradition is in the slightest degree to be trusted, Shakespeare must have commenced his metropolitan career. This Liberty, at a later period termed Holywell, derived its name from a sacred (A.-S. halig) well or fountain which took its rise in the marshy grounds situated to the west of the high street leading from Norton Folgate to Shoreditch Church,—mora in qua fons qui dicitur Haliwelle oritur, charter of A.D. 1189 printed in Dugdale's Monasticon Anglicanum, ed. 1682, p. 531. In Shakespeare's time, all veneration or respect for the well had disappeared. Stow speaks of it as "much decayed and marred with filthinesse purposely layd there for the heighthening of the ground for garden plots," Survay, ed. 1598, p. 14. It has long disappeared, but it was in existence as recently as 1745, its locality being marked in the first accurate survey of the parish of St. Leonard, Shoreditch, made in that year by Chassereau. At that period the well was situated in a field which was on the east of the Curtain Road and a little to the north of the junction of the Willow Walk with that road. The present Bateman's Row takes its name from the then owner of that field, and the site of the well is now one chain to the south of that Row and two chains to the east of the Curtain Road.

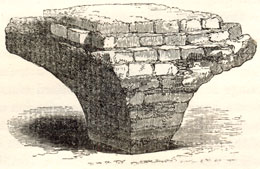

The lands in which the holy fountain was situated belonged for many generations to the Priory of Holywell, more frequently termed Halliwell Priory in the Elizabethan documents. This institution was suppressed and its church demolished in the time of Henry the Eighth, but the priory itself, converted into private residences, was suffered to remain. The larger portion of these buildings and some of the adjoining land were purchased by one Henry Webb in 1544, and are thus described in an old MS. index to the Patent Rolls preserved in the Record Office,—"unum messuagium cum pertinenciis infra scitum Prioratus de Halliwell, gardina cum pertinenciis, domos et edificia

cum pertinenciis, et tota domos et edificia vocata le Fratrie, claustrum vocatum le Cloyster et terram fundum et solum ejusdem, gardina vocata the Ladyes Gardens, unum gardinum vocatum le Prioresse Garden et unum columbare in eodem, ortum vocatum le Covent Orchard continentem unam acram, et omnia horrea, domos, brazinas etc. in tenura Johannis Foster, terram fundum et solum infra scitum predictum et ecclesie ejusdem et totam terram et solum totius capelle ibidem, totum curtilagium et terram vocata le Chappell Yard, et omina domos, edificia et gardina in tenura predicti Johannis Foster, domum vocatum le Washinghouse et stabulum ibidem, et totum horreum vocatum le Oatebarne, parcella ejusdem Prioratus de Halliwell." A small portion of this estate, that in which the Theatre was afterwards erected, belonged in the year 1576 to one Giles Allen. It was at this period that "James Burbage of London joyner" obtained from Allen a lease, dated 13 April, 1576, of houses and land situated between Finsbury Field and the public road from Bishopsgate to Shoreditch Church. The boundary of the leased estate on the west is described as "a bricke wall next unto the feildes commonly called Finsbury Feildes." James Burbage, by trade a joiner, but at this time a leading member of the Earl of Leicester's Company of Players, was the originator of theatrical buildings in England, for the successful promotion of which his earlier as well as his adopted profession were exactly suited. He obtained the lease referred to with this express object, Allen covenanting with him that, if he expended two hundred pounds upon the buildings already on the estate, he should be at liberty "to take downe and carrie awaie to his and their owne proper use all such buildinges and other thinges as should be builded, erected or sett upp, in or uppon the gardeines and voide grounde by the said indentures graunted, or anie parte therof, by the said Jeames his executors or assignes either for a theatre or playinge place or for anie other lawefull use for his or their commodities," Answer of Giles Allen in the suit of Burbage v. Allen, Court of Requests, 6 Febr. 42 Eliz. The lease was signed on April 13th, 1576, and Burbage must have commenced the erection of his theatre immediately afterwards. It was the earliest fabric of the kind ever built in this country, and emphatically designated The Theatre. By the summer of the following year it was a recognized centre of theatrical amusements. On the first of August, 1577, the Lords of the Privy Council directed a letter to be forwarded "to the L. Wentworth, Mr. of the Rolles, and Mr. Lieutenaunt of the Tower, signifieng unto them that for thavoiding of the sicknes likelie to happen through the heate of the weather and assemblies of the people of London to playes, her Highnes plesure is that as the L. Mayor hath taken order within the Citee, so they imediatlie upon the receipt of their 11. lettres shall take order with such as are and do use to play without the liberties of the Citee within that countie, as the Theater and such like, shall forbeare any more to play untill Mighelmas be past at the least, as they will aunswer to the contrarye," MS. Register of the Privy Council. The county here alluded to is Middlesex. This is the earliest notice of the Theatre yet discovered.

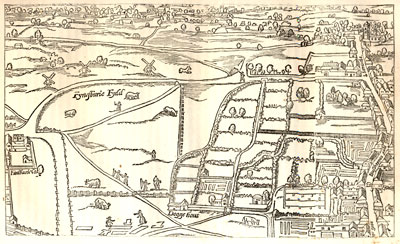

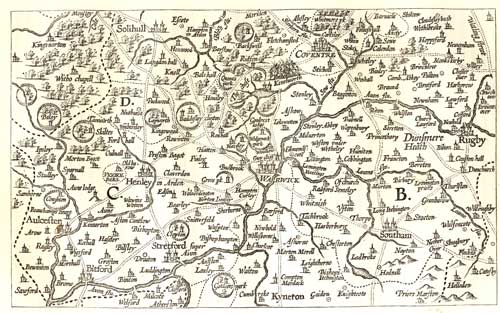

There is no ancient view of the district leased to Burbage in which the Theatre is introduced, but a general notion of the aspect of the locality may be gathered from the portion of the map of Aggas in which it is included. The perspective and measurements of that plan are unfortunately inaccurate, as may be ascertained by comparing it with the more correct but far less graphic delineation of the same locality in Braun's map, 1574, here reproduced. Both Aggas and Braun undoubtedly made use of one and the same earlier plan, but the work of the latter appears in some respects to be more / p.12 / scientifically executed. It is clear from Braun's map, tested by the later survey completed by Faithorne in 1658, that the eastern boundary of Finsbury Field was much nearer the highway to Shoreditch than might be inferred from the position assigned to it by Aggas. That boundary was also nearly parallel with the highway, and part of it seems to be the road or sewer which, in Aggas's map, extends from an opening on the right of the Dog-house to the lane near the spot where is to be observed a rustic with a spade on his shoulder walking towards Shoreditch. That part of the map which I have here termed a road or sewer may have been and most likely was a line of way by the side of an open ditch, that which was afterwards the Curtain Road; a supposition all but confirmed by a survey of the bounds of Finsbury Manor, taken in 1586, where the eastern boundary of that manor hereabouts is mentioned as the "common sewer and waye" which "goethe to the playehowse called the Theater." If this be the case, the north end of this ditch was the commencement of Holywell Lane, and the brick wall on the west of the Priory buildings was exactly opposite, the position of that wall being incorrectly represented in Aggas's map. Finsbury Field certainly included the meadow in which the three windmills were situated, as appears from a survey of the manor taken in 1567 printed in Stow's Survey of London, ed. 1633, p. 913; and it also extended to the vicinity of the Dog-house, as I find from a notice of it in Rot. Pat. 35 Hen. VIII. pars 16. The portion of the Field which joined Burbage's estate was of course much nearer the village of Shoreditch. At the time of the erection of the Theatre there were, as will be presently seen, more houses in the neighbourhood of the Priory than are shown in either of the early plans of Braun and Aggas. Others were erected by Burbage in the immediate vicinity of the Theatre. Witnesses were asked in 1602, "whither were the said newe howses standing in the said greate yarde, and neere and alonge the late greate howse called the Theater;" and one of them deposed that "the newe houses standing in the greate yard neere and along the Theatre, and also those other newe builded houses that are on the other syde of the sayd greate yard over and against the sayd former newe builded houses, were not at the costes and charges of Gyles Allen erected, builded or sett up, as he hath heard, but were so builded by the said James Burbage about xxviij. yeares agoe." There can be no doubt that Aggas's plan was completed some years before the erection either of these houses or of the Theatre. The portion of it which is here engraved is a minutely faithful copy from the original preserved at the Guildhall. In this plan the Royal Exchange, not completed till 1570, is introduced, but this clearly appears to be the result of an alteration made in the original block some years after the completion of the latter. A similar variation is to be observed in some copies of Braun's plan, in one of which, 1574, in my collection, that building is inserted evidently in the same plate from which other copies of that date, in which it does not occur, were taken. It should be borne in mind that great caution is requisite in the study of all the early London maps. Those of Aggas, Braun and Norden are the only plans of the time of Queen Elizabeth which are authentic, and care must be taken that reliable editions are consulted, there being several inaccurate copies and imitations of all of them.

Burbage gave a premium of £20 for the lease of 1576, the term being for twenty-one years at the annual rent of £14, and it was covenanted that if the lessee expended £200 on the property in certain specified directions he should, at any time before the expiration of ten years, be entitled to claim from Allen a new lease for

twenty-one years commencing from the date of the latter. A lease carrying out these terms, dated 1 November, 27 Elizabeth, 1585, was accordingly prepared by Burbage and submitted on that day to Allen, who, however, declined to execute. The extent of the property must have been comparatively limited, consisting merely of two gardens, four houses and a large barn, as appears from the following rather curious and minute description of parcels which occurs in the proposed deed of 1585,—"all thos two howses or tenementes with thappurtenaunces which, att the tyme of the sayde former demise made, weare in the severall tenures or occupacions of Johan Harrison, widowe, and John Dragon; and also all that howse or tenement with thappurtenances together with the gardyn grounde lyinge behinde parte of the same beinge then likewise in the occupacion of William Garnett, gardiner, which sayd gardyn plott dothe extende in bredthe from a greate stone walle there which doth inclose parte of the gardyn then or latlye beinge in the occupacion of the sayde Gyles unto the gardeyne ther then in the occupacion of Ewin Colfoxe, weaver, and in lengthe from the same howse or tenement unto a bricke wall ther next unto the feildes commonly called Finsbury Feildes; and also all that howse or tenemente with thappurtenances att the tyme of the sayde former demise made called or knowne by the name of the Mill-howse, together with the gardyn grounde lyinge behinde parte of the same, also att the tyme of the sayde former dimise made beinge in the tenure or occupacion of the foresayde Ewyn Colefoxe or of his assignes, which sayde gardyn grounde dothe extende in lengthe from the same house or tenement unto the forsayde bricke wall next unto the foresayde feildes; and also all those three upper romes with thappurtenaunces next adjoyninge to the foresayde Mill-house also beinge att the tyme of the sayde former dimise made in the occupacion of Thomas Dancaster, shomaker, or of his assignes; and also all the nether romes with thappurtenances lyinge under the same three upper romes and next adjoyninge also to the foresayde house or tenemente called the Mill-house, then also beinge in the severall tenurs or occupacions of Alice Dotridge, widowe, and Richarde Brockenburye or of ther assignes, together also with the gardyn grounde lyinge behynde the same, extendynge in lengthe from the same nether romes downe unto the forsayde bricke wall nexte unto the foresayde feildes, and then or late beinge also in the tenure or occupacion of the foresayde Alice Dotridge; and also so much of the grounde and soyle lyeinge and beinge afore all the tenementes or houses before graunted as extendethe in lengthe from the owtwarde parte of the foresayde tenementes beinge at the tyme of the makinge of the sayde former dimise in the occupacion of the foresayde Johan Harryson and John Dragon unto a ponde there beinge nexte unto the barne or stable then in the occupacion of the Right Honorable the Earle of Rutlande or of his assignes, and in bredthe from the foresayde tenemente or Mill-house to the midest of the well beinge afore the same tenementes; and also all that great barne with thappurtenances att the tyme of the makinge of the sayde former dimise made beinge in the severall occupacions of Hughe Richardes, inholder, and Robert Stoughton, butcher; and also a little peece of grounde then inclosed with a pale and next adjoyninge to the foresayde barne, and then or late before that in the occupacion of the sayde Roberte Stoughton, together also with all the grounde and soyle lyinge and beinge betwene the sayde neyther romes last before expressed and the foresayde greate barne and the foresayde ponde, that is to saye, extendinge in lengthe from the foresayde ponde unto a ditche beyonde the brick wall nexte the foresayde feildes; and also the sayde Gyles Allen and Sara his wyfe doe by / p.15 / thes presentes dimise, graunte and to farme lett, unto the sayde Jeames Burbage all the right, title and interest, which the sayde Gyles and Sara have, or ought to have, of, in or to all the groundes and soile lyeinge betwene the foresayde greate barne and the barne being at the tyme of the sayde former dimise in the occupacion of the Earle of Rutlande or of his assignes, extendeinge in lengthe from the foresayde ponde and from the foresayde stable or barne then in the occupacion of the foresayde Earle of Rutlande or of his assignes downe to the foresayde bricke wall next the foresayde feildes; and also the sayde Gyles and Sara doe by thes presentes demise, graunt and to fearme let, to the sayde Jeames all the sayde voide grounde lieynge and beinge betwixt the foresayde ditche and the foresayde brickwall extendinge in lenght

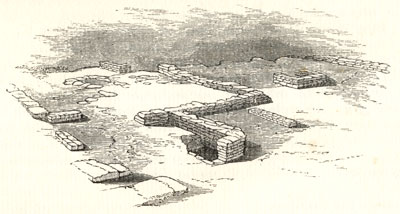

There is no doubt that the estate above described formed a portion of that which was purchased by Webb in 1544, and belonged to Allen in 1576, for in a paper in a suit instituted many years afterwards respecting "a piece of void ground" on the eastern boundary of the property leased to Burbage we are informed that Henry the Eighth granted to Henry Webb "a greate parte of the scite of the said Pryorie, and namely amongst other thinges all those barnes, stables, bruehowses, gardens and all other buildinges whatsoever, with theire appurtenaunces, lyinge and beinge within the scite, walles and precincte of the said Pryorye, on the West parte of the said Priorye, within the lower gate of the said Priorye, and all the ground and soyle by any wayes included within the walles and precincte of the said priorye extendinge from the said lower gate, of which ground the sayd yarde or peece of void ground into which it is supposed that the said Cuthbert Burbage hath wrongfully entered is parcell." This important evidence enables us to identify the exact locality of the Burbage estate, the southern boundary of which extended from the western side of the lower gate of the Priory to Finsbury Fields, the brick wall separating the latter from Burbage's property being represented in Aggas's map in a north-east direction from Holywell Lane on the west of the Priory buildings, though, as previously stated, the wall is placed in that map too near Shoreditch. The rustic with the spade on his shoulder who, in Aggas's view, is represented as walking towards Holywell Lane, is at a short distance from the south-western corner of Burbage's property. Somewhere near that corner the Theatre was undoubtedly situated. This opinion is confirmed by Stow, who, in his Survay of London, ed. 1598, p. 349, thus writes, speaking of the Priory,—"the Church being pulled downe, many houses have bene their builded for the lodgings of noblemen, of straungers borne and other; and neare thereunto are builded two publique houses for the acting and shewe of comedies, tragedies and histories, for recreation, whereof the one is called the Courtein, the other the Theatre, both standing on the south-west side towards the Field," that is, Finsbury Field. The "lower gate," mentioned in the record above quoted, was on the north side of Holywell Lane, and in a deposition taken in 1602, it is stated that the "Earle of Rutland and his assignes did ordinarily at theire pleasures chayne and barre up the lane called Holloway Lane leading from the greate streete of Shordich towardes the fieldes along before the gate of the said Pryory, and so kept the same so cheyned and barred up as a private foote / p.16 / way, and that the same lane then was not used as a common highway for carte or carriage." Other witnesses assert that no one was allowed "to passe with horse or carte" unless he had the Earl's special permission. It is, perhaps, not to be concluded from these statements that persons were not allowed to drive carts through the lane, but simply that the Earl took the ordinary precautions to retain it legally as a private road. The lower gate, though indistinctly rendered, may be observed in Aggas's map on the south of the west end of the Priory buildings, and upon land situated to the north-west of this gate the Theatre was erected. All this locality is now so completely altered, it being a dense assemblage of modern buildings, that hardly any real archæological interest attaches to it. The position of the Theatre, however, can be indicated with a near approach to accuracy. The ruins of the Priory were still visible in the last century in King John's Court on the north of Holywell Lane, and were incorrectly but popularly known as the remains of King John's Palace (Maitland's History of London, ed. 1739, p. 771). The ruins have disappeared, but the Court is still in existence, a circumstance which enables us to identify the locality of the Priory. It appears, therefore, from the evidences above cited, that the Theatre must have been situated a little to the north of Holywell Lane as nearly as possible on the site of what is now Deanes Mews. In digging recently for the foundations of a railway, which passes over some of the ground upon which the Priory stood, there were discovered the remains of the stone-work of one of the ancient entrance-doors. These few relics, now (1873) deposited outside an adjoining cottage, are most probably the only vestiges remaining of what was once the thriving and somewhat important Priory of Holywell.

Although the Theatre must have been situated near some of the houses on the Burbage estate, it was practically "in the fields," as is ascertained from indisputable evidences. Stockwood, in August, 1578, speaks of it as "the gorgeous playing place erected in the fieldes." Fleetwood, writing to Lord Burghley in June, 1584, says,— "that night I retorned to London, and found all the wardes full of watches; the cause thereof was for that very nere the Theatre or Curten, at the tyme of the playes, there laye a prentice sleping upon the grasse, and one Challes alias Grostock dyd turne upon the too upon the belly of the same prentice, wherupon the apprentice start up, and after wordes they fell to playne blowes," MS. Lansd. 41. The neighbourhood of the Theatre was occasionally visited by the common hangman, a circumstance which proves that there was an open space near the building. In the True Report of the Inditement &c. of Weldon, Hartley and Sutton, who suffred for High Treason in severall Places about the Citie of London on Saturday the Fifth of October, 1588, it is stated that "after Weldons execution the other prisoners were brought to Hollywell, nigh the Theater, where Hartley was to suffer." In Tarlton's Newes Out of Purgatorie, 1590, that celebrated actor is represented as knowing that the performance at the Theatre was finished when he "saw such concourse of people through the Fields;" and when Peter Streete removed the building in 1599, he was accused by Allen of injuring the neighbouring grass to the value of fourty shillings. There is a similar allusion to the herba Cutberti in proceedings in Burbage v. Ames, Coram Rege Roll, Hil. 41 Elizabeth, a suit respecting a small piece of land in the immediate locality. The Theatre was originally built on enclosed ground, but a pathway or road was afterwards made from it into the open fields. A witness deposed in 1602 that "shee doth not knowe anie ancient way into the fieldes but a way used after / p.17 / the building of the Theatre, which leadeth into the fieldes." Finally, there is the testimony of Gerard, who, in his pleasing work, the Herball, 1597, p. 804, after describing the ordinary crowfoot, adds,—"the second kind of crowfoot is like unto the precedent, saving that his leaves are fatter, thicker and greener, and his small twiggie stalkes stand upright, otherwise it is like; of which kinde it chanced that, walking in the fielde next unto the Theater by London, in company of a worshipfull marchant named master Nicholas Lete, I founde one of this kinde there with double flowers, which before that time I had not seene." Thus Shakespeare's observation of our wild flowers was not necessarily limited, as has been supposed, to his provincial experiences, the principal theatres existing in the earlier period of his metropolitan career having been situated in a rural suburb, and green fields being then within an easy walk from any part of London.

The quotation above given from Tarlton's Newes out of Purgatorie, 1590, shows that the usual access to the Theatre was through Finsbury Fields. There was certainly no regular path to it through the Lower Gate of the Priory, the old plans of the locality exhibiting its site as enclosed ground; and according to one witness, whose evidence was taken in 1602, Allen, previously to the erection of the Theatre, had no access to his premises from the south, but merely from the east and north. The testimony here alluded to was given in reply to the following interrogatory,— "whither had not the said Allen his servauntes, and such other tenauntes as he had, before those said newe buildinges were sett up and before the Theater was builded their ordinarie waie of going and coming in and out to his howse onely through that place or neere or over againste that place wheare the Theater stood into feildes and streetes, and not anie other waie, and how long is it since he or his did use anie other waie as you knowe or have heard." Mary Hobblethwayte of Shoreditch, who gave her age as 76 or thereabouts, deposed "that the said Allen his servauntes and tenentes, before those newe buildinges were sett up, and before the Theatre was builded, had theire ordinary way of going and coming to and from his house onely through a way directly towardes the North, inclosed on both sydes with a brick wall, leading to a Crosse neere unto the well called Dame Agnes a Cleeres Well, and that the way made into the fieldes from the Theatre was made since the Theatre was builded, as shee remembreth, and that the said Allen his servauntes and tenauntes had not any other way other then the way leading from his house to the High Streete of Shordich." On the other hand, there were witnesses examined at the same time who asserted that Allen had access to the fields by a path through or near the site of the Theatre before that building was erected. Leonard Jackson, aged 80, declared "that the said Allen his servauntes and others his tenauntes had, before those newe buildinges were sett up, and before the Theatre was builded, the ordinary way of going and comming in and out to his house through that place, or neere or over against that place where the Theatre stoode, and that he and they had also another way through his greate orchard into the High Streete of Shorditch, and that he hath used that way some xxx. yeares or xxxv. yeares or thereaboutes." Still more in detail but to a like effect is the deposition of John Rowse, aged 55, who stated that "the saide Allen his servauntes and other tenauntes there had, before those his newe buildinges were sett up and before the Theatre was builded, theire ordinary waie coming and going in and out to his house onely through that place, or neere or over against that place where the saide Theatre stoode into the fieldes, and that nowe and then he and some of his / p.18 / tenauntes did come in and out at the greate gate, and he doth remember this to be true, bycause that the said Allen nowe and then at his going into the country from Hollowell did give this examinates father, being appointed Porter of the house by his Lord Henry Earle of Rutland, for his paines, sometymes iij. s, sometymes iiij. s, and further he saieth that he hath knowne the said Allen and his servauntes use another way from his house through his long orchard into Hollowell Streete or Shorditch Streete, and this waie as he this examinate remembreth some xxx.ty yeares or thereaboutes." It must be borne in mind that the property affected by the rights of way investigated in these evidences consisted of the whole of Allen's estate before Burbage was his lessee.

It appears from Hobblethwayte's evidence that, after the Theatre was built, there was a road or path made from it on the west side into the fields. This road or path must have been made through the brick wall on the eastern boundary of Finsbury Fields, as is ascertained from a clause in the proposed lease from Allen to Burbage, 1585, and from an unpublished account of the boundaries of Finsbury Manor written in 1586, in which, after mentioning that the bounds of the manor on the south passed along the road which divided More Field from Mallow Field, the latter being the one to the east of the grounds of Finsbury Court, the writer proceeds to describe them as follows,—"and so alonge by the southe ende of the gardens adjoyninge to More Feld into a diche of watter called the Common Sewer which runnethe into More Diche, and from thence the same diche northewarde alonge one theaste side the gardens belonginge to John Worssopp, and so alonge one theaste side of twoo closes of the same John Worssopp nowe in the occupacion of Thomas Lee thelder, buttcher, for which gardens and closses the said John Worssopp payed the quit rent to the mannor of Fynsbury, as aperethe by the recorde, and so the same boundes goe over the highe waye close by a barren lately builded by one Niccolles, includinge the same barren, and so northe as the Common Sewer and waye goethe to the playehowse called the Theater and so tournethe by the same Common Sewer to Dame Agnes the Clere." The evidence of Hobblethwayte is confirmed by the testimony of Anne Thornes of Shoreditch, aged 74, who deposed,—"that shee cannott remember that Allen his servauntes or tenauntes had, before the said new buildinges were sett up or before the said Theatre was builded, theire ordinary way of going and comming unto his house onely through that place where the Theatre stoode into the fieldes or neere or over against that place; but shee hath heard that, since the building of the Theatre, there is a way made into the fieldes, and that the said Allen and his tenauntes have for a long tyme used another way out of the sayd scite of the Priory that the said Allen holdeth into the High Streete of Shorditch." Rowse's evidence proves that there could have been no regular access to the locality of the Theatre through the Lower Gate of the Priory in Holywell Lane, and very few indeed of the audience could have used the path which entered Allen's property to the north from the well of St. Agnes le Clair, which latter was not in the direction of any road used by persons coming from London. It follows that, in Shakespeare's time, the chief if not the only line of access to the Theatre was across the fields which lay to the west of the western boundary wall of the grounds of the dissolved Priory, and through those meadows, therefore, nearly all the visitors to the Theatre would arrive at their destination, most of them on foot but some no doubt riding "into the fieldes playes to behold," Davis's Epigrammes, 1599. This question of their route is not a subject of / p.19 / mere topographical curiosity, the conclusion here reached increasing the probability of there being some foundation for the tradition recorded by Davenant.

The Theatre appears to have been a very favourite place of amusement, especially with the more unruly section of the populace. There are several allusions to its crowded audiences and to the license which occasionally attended the entertainments, the disorder sometimes penetrating into the City itself. "By reason no playes were the same daye, all the Citie was quiet," observes the writer of a letter in June, 1584, MS. Lansd. 41. Stockwood, in a Sermon Preached at Paules Crosse the 24 of August, 1578, indignantly asks,—"wyll not a fylthye playe wyth the blast of a trumpette sooner call thyther a thousande than an houres tolling of a bell bring to the sermon a hundred ?—nay, even heere in the Citie, without it be at this place and some other certaine ordinarie audience, where shall you finde a reasonable company ?—whereas, if you resorte to the Theatre, the Curtayne and other places of playes in the Citie, you shall on the Lords Day have these places, with many other that I cannot recken, so full as possible they can throng;" and, in reference again to the desecration of the Sunday at the Theatre, he says,—"if playing in the Theatre or any other place in London, as there are by sixe that I know to many, be any of the Lordes wayes, whiche I suppose there is none so voide of knowledge in the world wil graunt, then not only it may but ought to be used; but if it be any of the wayes of man, it is no work for the Lords sabaoth, and therfore in no respecte tollerable on that daye." It was upon a Sunday, two years afterwards, in April, 1580, that there was a great disturbance at the same establishment, the only record of which that has come under my notice is in a letter from the Lord Mayor of London to the Privy Council dated April 12th,—"where it happened on Sundaie last that some great disorder was committed at the Theatre, I sent for the undershireve of Middlesex to understand the cercumstances, to the intent that by myself or by him I might have caused such redresse to be had as in dutie and discretion I might, and therefore did also send for the plaiers to have apered afore me, and the rather because those playes doe make assembles of cittizens and their familes of whome I have charge; but forasmuch as I understand that your Lordship with other of hir Majesties most honorable Counsell have entered into examination of that matter, I have surceassed to procede further, and do humbly refer the whole to your wisdomes and grave considerations; howbeit, I have further thought it my dutie to informe your Lordship, and therewith also to beseche to have in your honorable rememberance, that the players of playes which are used at the Theatre and other such places, and tumblers and such like, are a very superfluous sort of men and of suche facultie as the lawes have disalowed, and their exersise of those playes is a great hinderaunce of the service of God, who hath with His mighty hand so lately admonished us of oure earnest repentance," City of London MSS. The Lord Mayor here of course alludes to the great earthquake which had occurred a few days previously. In June, 1584, there was a disturbance just outside the Theatre, thus narrated in a letter to Lord Burghley,—"uppon Weddensdaye one Browne, a serving man in a blew coat, a shifting fellowe, havinge a perrelous witt of his owne, entending a sport if he cold have browght it to passe, did at Theater doore querell with certen poore boyes, handicraft prentises, and strooke somme of theym; and lastlie he, with his sword, wondeid and maymed one of the boyes upon the left hand, whereupon there assembled nere a thousand people;—this Browne dyd very cuninglie convey hymself awaye." The crowds of disorderly / p.20 / people frequenting the Theatre are thus alluded to in Tarlton's Newes out of Purgatorie, 1590,—"upon Whitson monday last I would needs to the Theatre to see a play, where, when I came, I founde such concourse of unrulye people that I thought it better solitary to walk in the fields then to intermeddle myselfe amongst such a great presse." In 1592, there was an apprehension that the London apprentices might indulge in riots on Midsummer-night, in consequence of which the following order was issued by the Lords of the Council,—"moreover for avoydinge of thes unlawfull assemblies in those quarters, yt is thoughte meete yow shall take order that there be noe playes used in anye place nere thereaboutes, as the Theator, Curtayne or other usuall places there where the same are comonly used, nor no other sorte of unlawfull or forbidden pastymes that drawe togeather the baser sorte of people, from henceforth untill the feast of St. Michaell," MS. Register of the Privy Council, 23 June, 1592. Another allusion to the throngs of the lower orders attracted by the entertainments at the Theatre occurs in a letter from the Lord Mayor of London to the Privy Council dated 13 September, 1595,—"Among other inconvenyences it is not the least that the refuse sort of evill disposed and ungodly people about this Cytie have oportunitie hearby to assemble together and to make their matches for all their lewd and ungodly practizes, being also the ordinary places for all maisterles men and vagabond persons that haunt the high waies to meet together and to recreate themselfes, whereof wee begin to have experienc again within these fiew daies since it pleased her highnes to revoke her comission graunted forthe to the Provost Marshall, for fear of home they retired themselfes for the time into other partes out of his precinct, but ar now retorned to their old haunt, and frequent the plaies, as their manner is, that ar daily shewed at the Theator and Bankside, whearof will follow the same inconveniences, whearof wee have had to much experienc heartofore, for preventing whearof wee ar humble suters to your good Ll. and the rest to direct your lettres to the Justices of Peac of Surrey and Middlesex for the present stay and finall suppressing of the said plaies as well at the Theator and Bankside as in all other places about the Cytie." It is clear from these testimonies that the Theatre attracted a large number of persons of questionable character to the locality, thus corroborating what has been previously stated respecting the degree of responsibility attached to those who undertook the care of the horses belonging to the more respectable portion of the audience.

Two years afterwards, the inconveniences attending the large numbers of people resorting to the Shoreditch theatres culminated in an order of the Privy Council for their removal, a decree which, like several others of a like kind emanating from the same body, was disregarded. The order appeared in the form of a letter to the Justices of Middlesex dated July 28th, 1597, the contents of which are recorded as follows in the Council Register,—"A lettre to Robert Wrothe, William Fleetwood, John Barne, Thomas Fowle and Richard Skevington esquire, and the rest of the Justices of Middlesex nerest to London; Her Majestie being informed that there are verie greate disorders committed in the common playhouses both by lewd matters that are handled on the stages, and by resorte and confluence of bad people, hathe given direction that not onlie no plaies shal be used within London or about the Citty or in any publique place during this tyme of sommer, but that also those playhouses that are erected and built only for suche purposes shal be plucked downe, namelie the Curtayne and the Theatre nere to Shorditch, or any other within that county; theis are therfore in her Majesties name to chardge and commaund you that you take present order there be / p.21 / no more plaies used in any publique place within three myles of the Citty untill Alhallontide next, and likewyse that you do send for the owner of the Curtayne Theatre or anie other common playhouse, and injoyne them by vertue hereof forthwith to plucke downe quite the stages, galleries and roomes that are made for people to stand in, and so to deface the same as they maie not be ymploied agayne to suche use, which yf they shall not speedely performe you shall advertyse us that order maie be taken to see the same don according to her Majesties pleasure and commaundment." This order appears to have been issued in consequence of representations made by the Lord Mayor in a letter written on the same day to the Privy Council, in which he observes,—"wee have fownd by th'examination of divers apprentices and other servantes whoe have confessed unto us that the saide staige playes were the very places of theire randevous appoynted by them to meete with such otheir as wear to joigne with them in theire designes and mutinus attemptes, beeinge allso the ordinarye places for maisterles men to come together to recreate themselves, for avoydinge wheareof wee are nowe againe most humble and earnest suitors to your honors to dirrect your lettres as well to ourselves as to the Justices of Peace of Surrey and Midlesex for the present staie and fynall suppressinge of the saide stage playes as well at the Theatre, Curten and Banckside, as in all other places in and abowt the Citie," City of London MSS. The players wisely erected all their regular theatres in the suburbs, the Mayor and Corporation of the City having been virulently opposed to the drama throughout the reigns of Elizabeth and James.

The crowds which flocked to places of entertainment were reasonably supposed to increase the danger of the spread of infection during the prevalence of an epidemic, and the Theatre and Curtain were sometimes ordered to be closed on that account. The Lord Mayor of London in a letter to Sir Francis Walsingham, dated May 3rd, 1583, thus writes in reference to the plague,—"Among other we finde one very great and dangerous inconvenience, the assemblie of people to playes, beare-bayting, fencers and prophane spectacles at the Theatre and Curtaine and other like places, to which doe resorte great multitudes of the basist sort of people and many enfected with sores runing on them, being out of our jurisdiction, and some whome we cannot descerne by any dilligence and which be otherwise perilous for contagion, biside the withdrawing from Gods service, the peril of ruines of so weake byldinges and the avancement of incontinencie and most ungodly confederacies," City of London MSS. In the spring of the year 1586 plays at the Theatre were prohibited on account of the danger of infection, as appears from the following note in the Privy Council Register under the date of May 11th,—"A lettre to the L. Maior; his l. is desired, according to his request made to their Lordshippes by his lettres of the vij.th of this present, to geve order for the restrayning of playes and interludes within and about the Cittie of London, for th'avoyding of infection feared to grow and increase this tyme of sommer by the comon assemblies of people at those places, and that their Lordshippes have taken the like order for the prohibiting of the use of playes at the Theater and th'other places about Newington out of his charge,"—MS. Register preserved at the Privy Council Office.

The preceding document of July, 1597, contains the latest notice of the Theatre in connexion with dramatic entertainments which has yet been discovered. It is alluded to in Skialetheia, published in the following year, 1598, as being then closed,—"but see yonder

One, like the unfrequented Theater,